“No other team plays under more political pressure than the Springboks” – Jake White, World Cup winning coach.

The story of South African rugby would not be completed without reflecting on the prevailing political issues.

The Afrikaners in South Africa came through the crucible of tough frontier life stretching over centuries and two bitterly fought wars of independence against the biggest imperial empire at the time, Great Britain. These were the people who Sir Arthur Conan Dolye described a follows:

“Take a community of Dutchmen of the type of those who defended themselves for fifty years against all the power of Spain at a time when Spain was the greatest power in the world. Intermix with them a strain of those inflexible French Huguenots who gave up home and fortune and left their country for ever at the time of the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The product must obviously be one of the most rugged, virile, unconquerable races ever seen upon earth. Take this formidable people and train them for seven generations in constant warfare against savage men and ferocious beasts, in circumstances under which no weakling could survive, place them so that they acquire exceptional skill with weapons and in horsemanship, give them a country which is eminently suited to the tactics of the huntsman, the marksman, and the rider. Then, finally, put a finer temper upon their military qualities by a dour fatalistic Old Testament religion and an ardent and consuming patriotism. Combine all these qualities and all these impulses in one individual, and you have the modern Boer—the most formidable antagonist who ever crossed the path of Imperial Britain. Our military history has largely consisted in our conflicts with France, but Napoleon and all his veterans have never treated us so roughly as these hard-bitten farmers with their ancient theology and their inconveniently modern rifles.”

Sir Winston Churchill (Footnote 1) wrote as such, after he was captured near Ladysmith, Natal by the Boers during the second “War of liberation”:

‘What men they were, these Boers! I thought of them as I had seen them in the morning riding forward through the rain–thousands of independent riflemen, thinking for themselves, possessed of beautiful weapons, led with skill, living as they rode without commissariat or transport or ammunition column, moving like the wind, and supported by iron constitutions’.

After the Second Anglo Boer War which lasted three years and ended in 1902, the Boers, or Afrikaners clawed themselves out of misery and poverty to eventually gain the political power in a unified South Africa, when the country became a union in 1910, with Boer general Louis Botha as first premier. The following is a quotation from a well-known website : “It (British atrocities committed against the Boer-Afrikaners during their independence struggle) not only irreparably damaged the British Empire and destroyed the economies of two independent countries, but directly led to the establishment of Apartheid in South Africa, by a paranoid Afrikaner nation.” In 1948 the National party came into power, entrenching whites in power with a policy called “apartheid”, which harmed the country politically, although it was primarily intended to enhance Afrikaner interest by keeping the races apart.

From the earliest days when they were introduced to the game, Afrikaners took to rugby like the proverbial fish to water. They used the sport not only as means to express themselves, but to prove to the outside world, especially the English, that they were better then their erstwhile enemies. Individualistic and often headstrong by nature, the indomitable Boer-Afrikaners found their raison d’etre in a team sport – rugby.

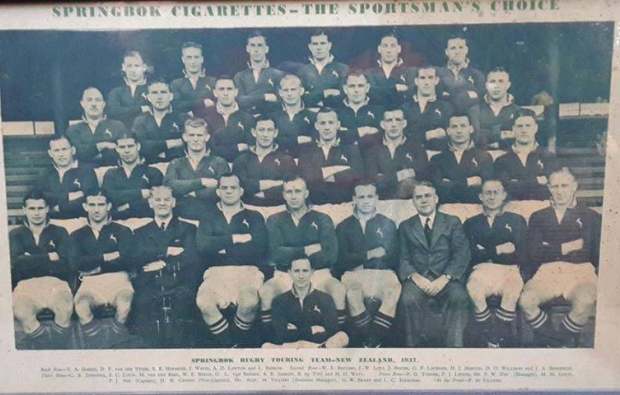

Rugby was a unifying force among the two white language groups in South Africa after the second Anglo Boer War, and nobody played a bigger part in this reconciliation process than Paul Roos, who led the first overseas tour by a South African representative team and under whose tutelage the term “Springbok” was coined and used for the first time.

Rightfully so, Roos deserves a special place in the first Springbok Rugby Quiz.

It is worth saying that the term “Springbok” was not restricted exclusively to rugby. South Africa’s fighting forces in World War 2 were fondly called “Springboks”, especially those – black and white – who fought Rommel’s “Afrika Korps” in North Africa. The “Springbok Legion” was established in 1941. It initially functioned as a “soldiers’ trade union” a non-discriminatory organization with a mixed race membership, which aimed to carry over in peace time the co-operation which existed between races. After the War, the Springbok Legion and the War Veterans Action Committee jointly launched the “Torch Commando” with Battle of Britain fighter ace Adolph Gysbert “Sailor” Malan – Afrikaans South African – as its president. Its primary aims: to protest against the absence of a common franchise for all South Africans and the abuse of power by the National Party government. Up until 1951, “coloured” people in the Cape Province could vote, until they were removed from the common/general roll. It is also noteworthy that leading members of the Springbok Legion joined the ANC in the liberation struggle. Those include Joe Slovo, Brian Bunting, Wolfie Kodesh, Jack Hodgson, and Fred Carneson.

Politics and sport are often intertwined. In 1980, USA president Jimmy Carter issued an ultimatum to the effect that his country would boycott the Olympic games in Moscow as a protest against the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan. The USSR ignored the ultimatum and the boycott stood. In their turn, the Russians responded by boycotting the 1984 Olympics held in Los Angeles.

South Africa did not escape political interference in sport. As the political pressure mounted on South Africa to change its domestic policy of segregation of the races, popularly referred to as “apartheid”, the country’s sports teams were made to suffer for the sins of its political masters. Sport was being used as a vehicle to force South Africa to reform. Already in 1964, the international Olympic Committee (IOC) withdrew South Africa’s invitation to compete when interior minister Jan de Klerk insisted that the team would not be racially integrated. Organisations such as HART – the acronym for “Halt all racist tours” and others disrupted sports events abroad.

On the local front, a Committee for International Recognition was formed by non-racial sportsmen in 1955 and was succeeded by the South African Sports Association (SASA) in 1958 and the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (SAN-ROC) in 1963 – to fight against racism in sport and press for international recognition of the non-racial sports bodies in South Africa. Their leadership was largely from the Indian and Coloured communities as the Africans were not practicing many of the codes of sport with international affiliations, writes ES Reddy, former director of the United Nations Centre against apartheid. He also accuses the New Zealand Olympic Committee of “declining to express regret” when protesting students were shot during the 1976 Soweto uprising.

Using slogans such as “no normal sport in an abnormal society”, organizations such as the highly politicized South African Council on Sport (SACOS, which was established in 1973), the National Olympic Committee of South Africa (NOCSA a black sports body) and South African National Olympic Committee, continued their efforts to isolate South African sport.

Pretoria Boys High old boy Peter Hain, chairman of the Stop the Seventy Tour, and his supporters disrupted the Springbok tour in 1969/70. Cries of “Paint them black and send them back” and “One, two, three four, we don’t want your racist tour”, echoed around the sports fields of the world as South Africans tried to ply their sporting trade. Athlete Zola Budd’s world record time for the 5000 metres was not ratified in January 1984, as the event was held outside the auspices of the IAAF. Gerhard Viviers, rugby commentator on the 1969/70 tour of the UK, announced that the demonstrators “earned” one pound per demonstration. As an aside, Viviers added that had he been a demonstrator, he would have bought himself some shampoo to wash his “disgustingly filthy hair”! Rather sardonically, British author Wallace Reyburn wrote a book about the tour to which he gave the sobering title “There was also some Rugby”.

That greatest of all rugby commentators, Scotsman Bill McLaren, described his experience of that tour in his autobiography, Talking of Rugby, as such:

“I was asked to provide commentary on their (the Springboks’) match against the Midland Counties (East) at Welford Road. I remember having to walk the gauntlet up a narrow channel lined on each side by policemen holding back the mob. Those policemen were covered in spittle, had hats knocked off, were kicked in places where no man should be kicked, and yet took it all with stoic calm. I couldn’t believe that people in the British Isles would behaved in that manner…. Constant noise outside the South Africans’ hotels to try and prevent them sleeping was another unbelievable ploy that sickened decent people.”

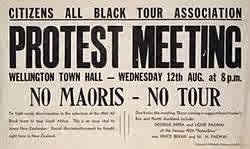

South Africa’s ruling Nationalist Party have to shoulder much of the blame for the international sports boycott. In a move which can only be described as shocking, not only for its substance, but also for its timing, Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd announced in his infamous Loskopdam speech on 4 September 1965 that future New Zealand teams would be welcome to tour the Republic – but without Maori players. This came while the Springboks themselves were touring New Zealand!

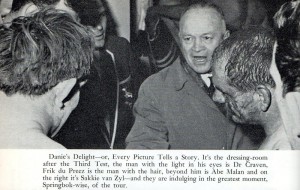

The shameful Basil D’Oliviera affair that played itself out in 1968 drove another nail in South Africa’s sports coffin. This led to the cancellation of the MCC tour on 24 September 1968. It is not surprising, therefore, that someone like Doctor Danie Craven, a champion for sport who fought unstintingly for South African rugby’s position on the international stage, held both the Nationalist and the Broederbond in absolute contempt.

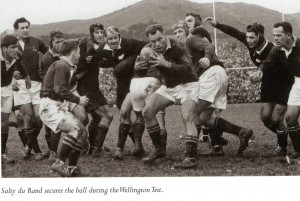

In the face of a rising groundswell to bring about change in South Africa, New Zealand refused to abandon their long rivalry with their old foes, mainly as they had up to 1996 – when South Africa was already a multi-party democracy – never won an away test series against the Springboks. The Kiwis maintained this contact with South Africa, but it has to be said that South African politics made it very difficult for New Zealand to choose sport above politics. Chris Laidlaw, touring South Africa with the All Blacks in 1970, describes in his autobiography, Mud in Your Eye, how harshly the (white) South African police treated non-white spectators in Kimberley during and after the match against Griquas.

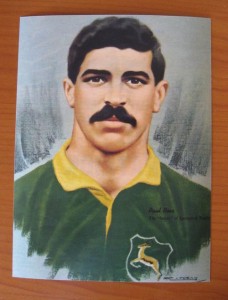

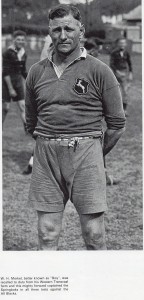

Boy Morkel epitomizes the uncompromising face of Springbok rugby.

In 1971, the Springboks toured Australia, amid considerable opposition. The South African team had to be transported in Australian Air Force planes because of trade union action. The State of Queensland declared a state of emergency during the tour, provoking a general strike by the trade unions.

Still, newly elected New Zealand Premier Rob Muldoon, allowed the 1976 All Blacks tour of South Africa to go ahead. As a result, 21 African countries boycotted the 1976 Summer Olympics in 1976.

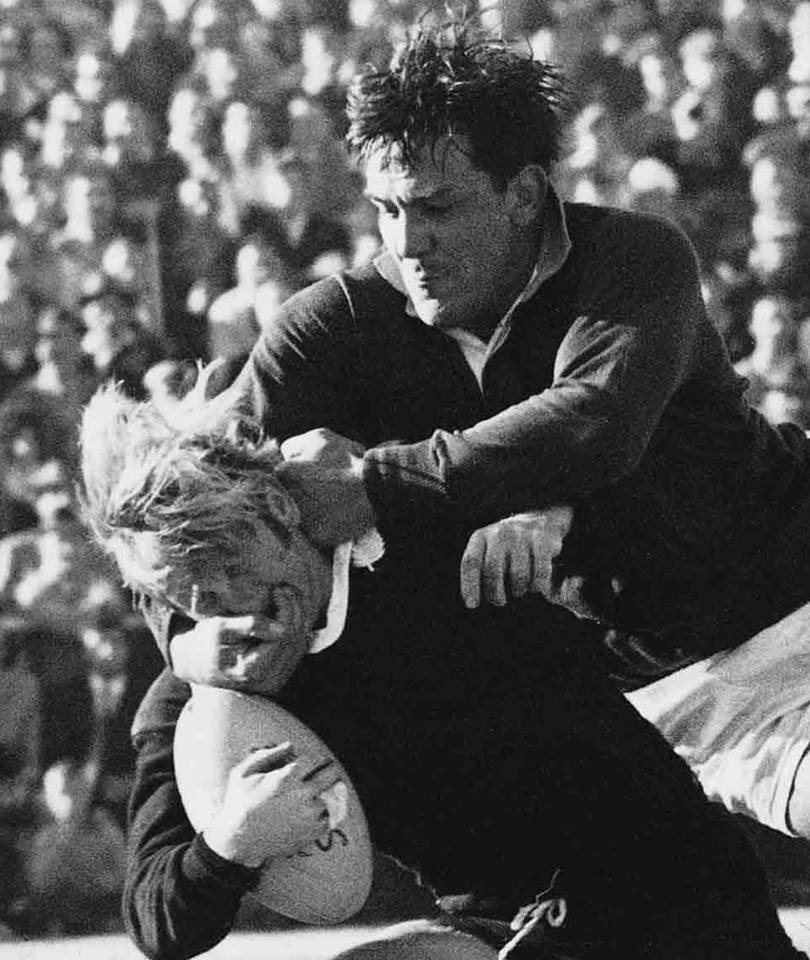

South Africa dominated world rugby for decades. The key to their success has often been an all-conquering pack. Chris Koch (with ball) was a mighty prop whose career stretched over three decades: 1949 – 1960.

Under the Gleneagles Agreement, endorsed by Commonwealth leaders in 1977, it was decided that all sporting contact with South Africa must be discouraged.

I started my working life as a TV journalist for SABC. 1979 was a watershed year for South African sport in general and rugby in particular. The Barbarians rugby team was departing from Jan Smuts Airport just after the Currie Cup final at Newlands featuring Western Province and Northern Transvaal, which ended in a 15-a1l draw. I arrived at the departure hall to find the players saying goodbye to their loved ones and well-wishers. Rob Louw, Western Province flanker was in good spirits. “Ons het ‘n halwe beker gewen”, (literally, “We won half a cup”) quipped the jovial Louw. Among the milling throng of passengers, well-wishers and officials, I picked out picked out the engaging and charismatic Chick Henderson, manager of this pioneering team. In the interview, Henderson, a former Scottish international and Transvaal no 8, proudly told the author of this book that his was the first fully representative South African rugby team in history to have in its ranks players from all South Africa’s population groups.

The team was well received by rugby fans. After beating Devon in the opening match on 3 October 1979, the touring side received a standing ovation from a 2000-strong crowd, the BBC reported. There were protesters. Some bore posters which read: “Selection on merit, not colour”, which would have been appropriate in another era. (Footnote 3)

This groundbreaking tour opened the door for the 1980 British Lions (they were subsequently called British and Irish Lions) to tour South Africa. Springbok captain Morné du Plessis went on record to thank the team for withstanding the political pressure “to allow us to wear our beloved green-and-gold again.” Politically frustrated, some people of colour chose to support the opposition. There was often jeering in the “non-white” stands – inevitably behind the goalposts – when a South African player kicked for goal.

This groundbreaking tour opened the door for the 1980 British Lions (they were subsequently called British and Irish Lions) to tour South Africa. Springbok captain Morné du Plessis went on record to thank the team for withstanding the political pressure “to allow us to wear our beloved green-and-gold again.” Politically frustrated, some people of colour chose to support the opposition. There was often jeering in the “non-white” stands – inevitably behind the goalposts – when a South African player kicked for goal.

Then came the calamitous tour by Wynand Claassen’s team in 1981. New Zealand as a country was torn apart. Circling Eden Park, Auckland, crazed pilot Marx Jones at times flew lower than the goal posts while his “bombardier” Grant Cole dropped flour bombs onto the field an into the stands from his Cessna while the third and final test was being played. Cole managed to score a direct “hit” on All Black prop Gary Knight and narrowly missed Springboks Gerrie Germishuys and Danie Gerber. At least eight spectators were also hit.

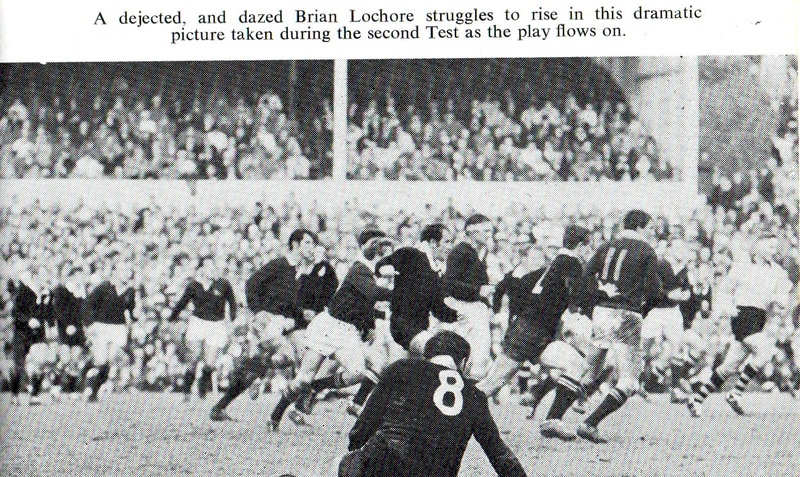

The 1981 Springbok tour ripped the very fabric of New Zealand society apart. Here, All Black Gary Knight has just been “decked” by a flour bomb hurled from a circling Cessna (see photo below).

Reflecting on the 1981 tour, hardcore rugby men and women to this day hold the view that the anti-tour movement were mostly socialist subversives that were intent on imposing their new age values on the rugby world. From their perspective, the tour was a triumph for the rights of the individual to choose despite opposing views trying to remove that right. “Those were the good old days, when men were rugby players, and protesters were nancy boys, and hippies”, says one critic on a popular rugby website. “Muldoon knew they would not vote for him anyway, so why not have a Springbok tour and get the Red Squad to beat them up with long batons,” says the same critic.

No team had ever endured so much political pressure as the 1981 Springboks. The third test was probably the most dramatic international match ever played. This photo says it all. A demented pilot swooped low over Eden Park while his “bombardier” took potshots at the players. At least eight spectators were co-lateral damage that added to his tally of direct hits.

England sent a fully-fledged team to the embattled Republic in 1984; but sport remained the convenient means to punish South Africans for their country’s political sins.

Danie Gerber was arguably the greatest centre who ever touched an oval ball. Political discrimination against South African sportsmen and women deprived the world from seeing Gerber on the world stage for many years.

The first official Rugby World Cup was staged in New Zealand in 1987 – without South Africa. Just one year previously, South Africa defeated a powerful New Zealand team which was effectively was a full-blown All Black team. The majority of the team that won the first World Cup played the Springboks in 1986. In a supreme example of hypocrisy, the International Rugby Board invited the USSR, where human rights were perpetually violated by a system called communism, to play in the 1987 Word Cup. France reportedly approached the USSR before the tournament on the issue of South Africa’s participation. The Soviets made it clear that they would not be happy to participate if South Africa was invited suggests author Chris Thau. Although a rugby superpower, South Africa ended up being left off the guest list. In a bizarre twist, the Soviets decided to pull out at the last minute anyway.

Except for a two test series against a “World Invitation XV” in 1989, South African rugby was deprived of any full international competition between the Kiwi visit in 1986, and the re-entry test in 1992, when ironically, the Springboks faced New Zealand at Ellispark again. True sportsmen and women the world over lamented South Africa’s isolation.

Even merely attending a match that involved South Africans, brought about its own risks. Again, Bill McLaren:

Even merely attending a match that involved South Africans, brought about its own risks. Again, Bill McLaren:

“Bette [Bill McLaren’s wife] and I were referred to as ‘racist scum’ on our way down to Mansfield Park to see the South African Barbarians play in 1979 – a tour party comprising equal numbers of coloureds, blacks and whites.

While deploring what he called South Africa’s “unacceptable racist policy”, Maclaren said “it has been a disgrace that a world Rugby Union power (the Springboks) has been eliminated from world competition for all those years”.

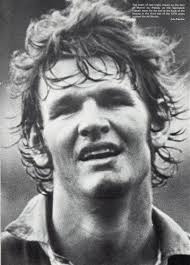

When steel meets steel: Moaner van Heerden (Springboks) and Ian Kirkpatrick (All Blacks) exchanging pleasantries in 1976.

Then, the defining moment came when President FW de Klerk (Footnote 4) released Nelson Mandela and un-banned the African National Congress. Mr Mandela walked out of jail on 11 February 1990 and South Africa was never the same again. And South Africa could participate on the international stage once more.

With the advent of black majority rule the South African Rugby Union, SARU, previously known as the South African Coloured Rugby Football Board, combined with the (previously white dominated) South African Rugby Board, or SARB in 1992. The new, amalgamated body was henceforth called the South African Rugby Union, or SARU. The emblem of the new body sported a Protea flower – the emblem of the old “coloured” rugby board – and the well-know Springbok. (Footnote 5)

Nelson Mandela became president in 1994. The country was gripped by euphoria.

However, certain radicals, masquerading as “sports administrators” saw Mandela’s election as their opportunity to have the Springbok emblem – then rightly or wrongly, perceived as a symbol of white supremacy or “baasskap” – removed from the shirts of South Africa’s sports representatives.

Concerned about the blatant abuse of certain unscrupulous individuals who were out to abuse sport for their own selfish and dubious political gains in the new South Africa, this correspondent determined to do something.

The way I saw it, the Springbok was for everybody. Even blacks and coloureds wanted to be called Springboks at some point in our collective history. The first coloured national team used the Springbok as its emblem in 1939 and the first black national team used it in 1950.

The way I saw it, the Springbok was for everybody. Even blacks and coloureds wanted to be called Springboks at some point in our collective history. The first coloured national team used the Springbok as its emblem in 1939 and the first black national team used it in 1950.

Now, in the winter of 1994, shortly after Mr Mandela’s inauguration as president of the new South Africa on 10 May 1994 a white man of medium build, of French Huguenot heritage and in his early 40’s, was gunning his light blue Citi-Golf to the Union Buildings, which housed the President’s office. He was in a race against time. The Springboks’ first match with Mandela as President was imminently due. The team was squaring off against England on 4 June. The driver of the blue Golf found paring some distance from the Union Buildings’ imposing façade. Walking briskly to the entrance, he arrived at reception and presented the secretary with an A-4 size, brown civil service-type envelope bearing the standard lettering Amptelik/Official.

At the time I was based in the South African Department of Water Affairs’ headquarters in the Residensie Building in Schoeman Street, Pretoria, officially on the payroll of the Trans-Caledon Tunnel authority and seconded to the Joint Permanent Technical Commission, a bi-mutual body overseeing the construction of the Lesotho Higlands Water Project.

I drafted a letter, appealing to Mandela not to allow the Springbok emblem to become a political plaything in the hands of those who cared nothing for sport. I briefly outlined South Africa’s rich and colourful rugby history, highlighting that it was under the Springbok emblem that our national team dominated world rugby for decades, that this emblem was synonymous with the country’s rugby supremacy and how our opponents feared and respected this emblem. I then pointed out to Mandela that thousands of black people made a living out of selling Springbok memorabilia such as ties, badges, cushions, flags, posters and such like. Finally, I stressed that by embracing the Springbok emblem, he would get the support of the white population and forge the entire South Africa into one unified nation. This was, en bref, the contents of the letter I dropped off at the Union Buildings that day in 1994.

I had scribbled on this government envelope the words URGENT – PLEASE HAND DELIVER. “This is for Mr Mandela. It is extremely important”, I said as I arrived at the President’s reception. “Yes, I’ll make sure the President gets this”, came the re-assuring reply.

I had scribbled on this government envelope the words URGENT – PLEASE HAND DELIVER. “This is for Mr Mandela. It is extremely important”, I said as I arrived at the President’s reception. “Yes, I’ll make sure the President gets this”, came the re-assuring reply.

I cannot claim that my letter had any effect on Mr Mandela’s subsequent announcement, or even that it affected his way of thinking. What is factual is that shortly afterwards, in an act of great statesmanship, the President announced on TV that the Springbok emblem will remain in use for rugby. Clint Eastwood depicts in a dramatic scene in his gripping movie Invictus how Mandela arrives uninvited at a meeting of the ANC National Executive where some radicals were hell-bent to get rid of this hated antelope, and nipped any further efforts to eliminate the emblem, in the bud. It is a matter of historical record that Mandela defeated Mluleki George’s and Makhenkesi Arnold Stofile malicious efforts to “kill” the ‘Bok.

Nelson Mandela united the country as never before when he donned a Springbok jersey as he handed Francois Pienaar the World Cup after the grueling final against New Zealand in 1995. After that epic win, Dan Qeqe, the veteran anti-apartheid sports campaigner and “father of black rugby” in South Africa, said: “I never had the chance to test myself against the white rugby greats, but today we play together, and the Springboks play for all of us.”

There is still political interference in South African sport. Frequently, an ANC government minister lashes out against the fact that there are too many “whites” in the team. Quotas, and rumours about quotas abound. Some hardliners demand that the team must be only “black” or “coloured”. Some black radicals were outraged when Oregan Hoskins, a “coloured” man, was elected President of SARU. (Footnote 6.) Accusations flew back and forth. “I am too black”, one defeated candidate was quoted as saying. “I am black enough”, came the reported Hoskins retort. The Springbok is at times at the mercy of opportunistic individuals like Butana Komphela, chairing the Parliamentary Sports Portfolio Committee and a politician with more mouth than meaning, as sports writer Kevin McCullum puts it.

In August 2015, just before the departure of the Springbok team to participate in the World Cup Cup Tournament held in the UK, all hell broke loose when COSATU claimed that black Springboks complained to them that coach Heyneka Meyers was discriminating against them. The players themselves denied those claims. Not surprisingly, it is COSATU’s oft-stated aim to have all all-black Springbok team.

In what were sometimes attempts thinly-disguised attempts to appease the politicians, SARU had previously appointed token black administrators, who, smartly attired in their gifted Springbok jerseys and hardly caring two hoots for sport in general and rugby in particular, decorated the stands at Newlands and Ellispark. Such attempts at window-dressing are in my view misguided and do nothing for sport in South Africa.

In what were sometimes attempts thinly-disguised attempts to appease the politicians, SARU had previously appointed token black administrators, who, smartly attired in their gifted Springbok jerseys and hardly caring two hoots for sport in general and rugby in particular, decorated the stands at Newlands and Ellispark. Such attempts at window-dressing are in my view misguided and do nothing for sport in South Africa.

To coach the Springboks is literally to occupy the hottest seat in world sport. Coaches of the national team seem to succeed each other in rapid succession. Even success is no guarantee that you will keep your position. Jake White won the World Cup but was not reinstated as coach. Nick Mallet recorded 16 wins on the trot and was then summarily fired. Gerrie Sonnekus was appointed coach but did not coach the ‘Boks in a single test. A test series defeat to the All Blacks in New Zealand cost Ian McIntosh his job after he had repeatedly clashed with former SA Rugby supremo Louis Luyt over interference in team selection, the latter favouring Transvaal players while McIntosh fought for Sharks players who had played under him at King’s Park. He was fired barely 14 months into the job, along with team manager Jannie Engelbrecht. And so on.

There are still some who hate the Springbok emblem, most of them South Africans. It is said that each time the Springboks take the field they play for their very identity.

When I returned from France to write this book, I bought a small house near the southern tip of Africa. There, I made an astonishing discovery. The hut next to the house had old South African Railways windows. The Springbok emblem emblazed on those windows seemed to jump out at me when I moved in. I don’t believe this to be a coincidence. I believe this to be a serendipitous, a pointer.

I, and millions of other true sports lovers globally, hope the Springbok lives forever.

Footnote 1: It is not commonly known that the great British statesman was an avid rugby fan. When South Africa played England on the first Springbok tour in 1906/7 the match was played in atrocious conditions and ended in a draw. The media were upset with the result and led a campaign to have the test replayed, even in calling the Under Secretary of State for Colonies at the time to say his peace. He was none other then Winston Churchill himself. England’s try in this match was scored by Freddie Brookes who himself played in the Springbok trials and was considered the second best wing in South Africa. Had he qualified for South African residency, he would have been a certainty for Paul Roos’ pioneers. (Ref The Carolin Papers. A Diary of the 1906\07 Tour. Compiled and Edited By Lappe Laubscher and Gideon Nieman 1990.)

Footnote 2: John Hamilton “Chick” Henderson was born in Johannesburg and studied at Michaelhouse, the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) and Oxford University. He played 9 tests for Scotland and was a founder member of the Quaggas Rugby Club and life member of the South African Barbarians. Seventeen out of Henderson’s 24 Barbarians represented either provincial or invitational sides that played against the touring Lions the following year, 1980. Seven members of the touring party went on to gain full Springbok status: Martiens le Roux, Ewoud Malan, Rob Louw, Divan Serfontein, Errol Tobias, Hennie Bekker and De Villiers Visser.

Footnote 3: Speaking before the match against the South African Barbarians on 3 October 1979, Devon skipper John Lockyer said “We’re being criticised for playing against the South Africans, yet nobody seems to condemn the staging of the Olympic Games in a repressive country like Russia.” Earlier, he stressed that because the South African side was a multi-racial team he saw it is a breakthrough for South African sport.

Footnote 4: The author was the journalist who interviewed De Klerk for his first TV appearance in October 1977. Whites supported De Klerk’s reforms not only to end discrimination, but also because it would end the sporting isolation and they could see their own Springboks in action again.

Footnote 5: The Protea was also used as the official emblem for South African universities teams. This included the men’s and women’s hockey teams which were announced after the annual South African Universities tournament. The author represented Free State University at three “SAU”s – 1975, ’76 and ’77. Playing goalkeeper, he was up against three Springboks in succession, David Reid-Ross of Stellenbosch, (whose brother Lindsay was nicknamed “Riff Raff” after the character in the musical “The Rocky Horror Picture Show”), “Ponky” Firer of Wits (a medical doctor) and Maurice Mars of UCT, who succeeded another Springbok, Ian Richter. So it may be said that it took three or four Springboks to keep him out of the “Proteas” team!

Footnote 6: Unlike in the UK, the USA and elsewhere, the term “coloured” in South Africa denotes people of mixed descent.